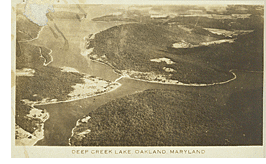

History of Deep Creek Lake

Deep Creek Lake has a long history of famous individuals and thoughtful thinkers coming to enjoy the shores of the lake. Make your next getaway to Deep Creek Lake.

Henry Ford and Thomas Edison — a friendship of giants

By Patricia Zacharias / The Detroit News

Thomas Alva Edison, the wizard of Menlo Park, was an inventive genius who also was capable of seeing and encouraging genius in others — a fact that may have led Henry Ford to spark the automobile age, and certainly cemented a 35-year friendship between the two giants.

As a young man on his father’s farm in Dearborn, Henry Ford had followed Thomas Edison’s career. Henry took a job at the Edison Illuminating Company, which later became Detroit Edison, and soon worked his way up to chief engineer.

In 1896, Ford and Alex Dow attended a company-sponsored convention in Manhattan Beach, New York. Edison was the guest of honor at the evening’s banquet. Alex Dow pointed out Ford to Edison, telling him “There’s a young fellow who has made a gas car.” Edison asked young Henry Ford a host of questions and when the interview was over, Edison emphasized his satisfaction by banging his fist down on the table. “Young man,” he said, “that’s the thing! You have it! Your car is self-contained and carries its own power plant.”

Years later, Ford, reflecting on their first meeting, said in a newspaper interview, “That bang on the table was worth worlds to me. No man up to then had given me any encouragement. I had hoped that I was headed right. Sometimes I knew that I was, sometimes I only wondered, but here, all at once and out of a clear sky, the greatest inventive genius in the world had given me complete approval. The man who knew most about electricity in the world had said that for the purpose, my gas motor was better than any electric motor could be.”

Ford never forgot those words of encouragement. After that initial meeting, Ford was always very close to Edison. When Ford became a wealthy industrialist, he cooperated with Edison in technical and scientific projects. He convinced Edison to devote significant research to finding a substitute for rubber.

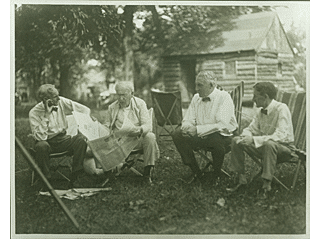

Together with John Burroughs, naturalist Luther Burbank, Harvey Firestone and occasionally, President Harding, Ford and Edison participated in a series of camping trips. A major source of fun for Ford and Edison was building dams on small streams and examining old mills for a calculation of the power output.

“They think in terms of power,” Firestone wrote. After his first experience with the Nature Club, President Harding joined the group whenever he could.

En route to a new campsite on a rainy day, the Lincoln touring car carrying Harding, Ford, Edison, Firestone and naturalist Luther Burbank bogged down in deep mud on a back road in West Virginia. Ford’s chauffeur went for help and returned with a farmer driving an ancient Model T. After the Lincoln was yanked from the mire, Ford was the first to shake the farmer’s hand.

“I guess you don’t know me but I’m Henry Ford. I made the car you’re driving.”

Firestone chimed in, “I’m the man who made those tires.” Then he introduced two of the campers: “Meet the man who invented the electric light — and the President of the United States.”

Luther Burbank was the last to shake hands. “I guess you don’t know me either?” he asked.

“No,” said the farmer, “but if you’re the same kind of liar as these other darn fools, I wouldn’t be surprised if you said you was Santa Claus.”

The vagabonds camping trip ended following the death of President Harding.

Edison, on the advice of his doctors, left his home in Menlo Park, N.J., for the warmer climate of Fort Myers, Fla. As would be expected of a man with 1,097 patented inventions, Edison outfitted the home with all kinds of novelties. There was an intercom system which he mischievously used to startle guests, and lights in the closet that blinked on automatically whenever the doors were opened. Edison also had the kitchen built in another building instead of the main house because he didn’t like to smell food cooking.

Ford was a regular visitor. In 1916, when the seven-bedroom home next door became available, Ford bought it. A wooden fence separated the two estates, but the gate always stood open and became known as the “friendship gate.” When Edison’s doctors ordered him into a wheelchair in the last years of his life, Ford, still brisk and active, bought one too so they could race around the grounds together.

In October 1929, on the 50th anniversary of the light bulb, Ford established the Edison Institute, which now operates Greenfield Village and Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn.

Even the rainy weather that October couldn’t put a damper on the festivities. Crowds lined 30 miles of Detroit streets to cheer Edison, President Hoover and 500 nationally and internationally known guests as they drove to the museum.

The ceremonies featured the re-enactment of the invention of the first successful incandescent bulb in the original Menlo Park laboratory, which had been moved by Henry Ford with other significant buildings to the Village.

Ford had brought in seven railroad cars of New Jersey soil to place around the buildings for complete accuracy. He even tried to get an old elm tree that stood near the door of the lab, but had to settle for a cutting of the old tree planted in the same spot.

Edison was pleased with Ford’s efforts, remarking that Ford got everything 99-9/10ths perfect. The inaccuracy, he told Ford, was that “our floor was never this clean.”

Ford and Edison’s assistant, Francis Jehl, who was with Edison when he developed his successful incandescent lamp, helped in the re-enactment. Nationwide, people turned on their electric lights in honor of the historic event. Later in the banquet hall, Edison stood up to speak, his snow-white hair disheveled, his hands and voice a bit shaky.

“I would be embarrassed at the honors that are being heaped upon me this unforgettable night were it not for the fact that in honoring me, you are also honoring that vast army of thinkers and workers of the past. If I have helped spur men to greater effort, if our work has widened the horizon of thousands of men and given a measure of happiness in the world, I am content.”

His last words were for Henry Ford. “I can only say that in the fullest meaning of the term, he is my friend.”

Bibliographic Note: Edison As I Know Him, by Henry Ford; Edison, Inventing the Century, by Neil Baldwin; Detroit’s Coming of Age, by Don Lochbiler and the clip and photo files of The Detroit News.

(This story was compiled using clip and photo files of The Detroit News.)

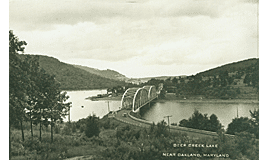

Oakland Maryland

The name “Oakland” was the suggestion of Ingaba McCarty, daughter of Edward McCarty. He had subdivided some of his land into a series of building lots, and was seeking a name for the proposed community to be built on the lots in 1849. Thus, Oakland developed from the original sub-division of the McCarty land. However, the McCarty’s were not the first settlers in this area.

The name “Oakland” was the suggestion of Ingaba McCarty, daughter of Edward McCarty. He had subdivided some of his land into a series of building lots, and was seeking a name for the proposed community to be built on the lots in 1849. Thus, Oakland developed from the original sub-division of the McCarty land. However, the McCarty’s were not the first settlers in this area.

Three Indian trails came together just west of Oakland in the Washington Spring area. There was a large Indian camp in there, where the Indians came to hunt and fish and trade with other Indians for hundreds of years. It wasn’t until the 1790’s that a man named Boyle built a cabin in the same area. He was the first white man to settle in the immediate area of Oakland.

In 1851, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad came through Oakland, and from that time onward, the town really began to grow. In 1862 it was incorporated as a town with its own form of government. However, the first leader of the town council was called a “Burgess”, and it was not until 1886 that they were called “Mayor”. After Garrett County was formed in 1872, Oakland was chosen as the county seat.

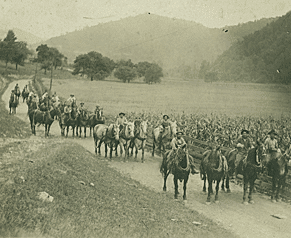

During the Civil War, Oakland was in union territory, but that did not prevent Confederate soldiers from raiding the town on April 24, 1863. Later, two famous Union Generals lived in Oakland: General Crook and General Kelly.

During the Civil War, Oakland was in union territory, but that did not prevent Confederate soldiers from raiding the town on April 24, 1863. Later, two famous Union Generals lived in Oakland: General Crook and General Kelly.

Oakland has always had an excellent climate in the summer months, and two well-known hotels were built in the town. The first one was the Glades Hotel, constructed in the late 1850’s. It was followed by the Oakland Hotel in 1875, which was owned by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

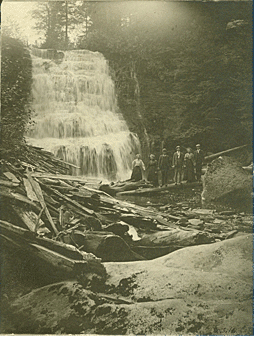

After the Civil War ended, the lumber business in the area around Oakland brought in a lot of business and the town grew larger. Lumber was followed by coal mining in the 1900’s. Since that time, other businesses have increased the size of the town.

Unfortunately, the town has not been free from disasters. The first was the flood of 1896, and it was followed by a series of floods, which finally ended in 1970 with the completion of the flood impoundment dams. Downtown Oakland has also had two disastrous fires. The first was in 1898; the second in 1994. Each one of them destroyed business places in the tow

Oakland Railroad Station

The original railroad station in Oakland was built when the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad came through this part of Garrett County in 1851. The entrance of the railroad to this part of the county produced an upturn in the economy of the community and Oakland began to increase in size. Across the station, a hotel was built around 1855, and was called the Glades Hotel. (This part of Garrett County was known as “The Glades” or sometimes “Yough Glades”.) Passenger trains would stop in the Oakland station long enough to allow passengers to eat meals at the Glades Hotel.

The original railroad station in Oakland was built when the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad came through this part of Garrett County in 1851. The entrance of the railroad to this part of the county produced an upturn in the economy of the community and Oakland began to increase in size. Across the station, a hotel was built around 1855, and was called the Glades Hotel. (This part of Garrett County was known as “The Glades” or sometimes “Yough Glades”.) Passenger trains would stop in the Oakland station long enough to allow passengers to eat meals at the Glades Hotel.

In 1875, the Railroad built a large resort hotel on the hillside across from the station, and a bridge connected the station platform with the walkways and roads in the hotel grounds. The wooden platform was eventually extended all the way up the east side of the tracks to the Second Street railroad crossing.

Unfortunately, the Glades Hotel burned down in 1884, and while burning, set fire to the Oakland station, destroying it at the same time. Since the station was an important part of the Oakland Hotel complex, a second station was built in 1884 and it is the present building.

Unfortunately, the Glades Hotel burned down in 1884, and while burning, set fire to the Oakland station, destroying it at the same time. Since the station was an important part of the Oakland Hotel complex, a second station was built in 1884 and it is the present building.

At one time, the railroad station was a busy place. A telegraph office was installed, and “train orders” were issued through this telegraph office. It also served as western Union telegraph office for people of Oakland. There was a large water tank beside the station to refill the supply of steam locomotives passing through. The Railway Express Agency operated from the baggage room of the station. (Today, UPS handles this kind of business.)

The last regular eastbound Baltimore and Ohio passenger train departed from Oakland on April 30, 1971. After that, Amtrak operated trains through Oakland for the next five years. Eventually, the station was closed as a passenger station and used as headquarters for railroad maintenance and signal gangs. Today it is run as a visitor’s center.

Accident, Maryland

WHY OUR TOWN IS CALLED “ACCIDENT,” FROM THE MAYOR AND TOWN COUNCIL

Following is the legend most frequently told by the local citizens:

About the year 1751, a grant of land was given to Mr. George Deakins by King George II of England in payment of a debt. According to the terms, Mr. Eakins was to receive 600 acres of land anywhere in Western Maryland he chose. Mr. Deakins sent out two corps of engineers, each without knowledge of the other group, to survey the best land in this section that contained 600 acres.

After the survey, the engineers returned with their maps of the plots they had surveyed. To their surprise, they discovered that they had a surveyed a tract of land starting at the same tall oak tree and returning to the starting point. Mr. Deakins chose this plot of ground and had it patented “The Accident Tract” – hence, the name of the town.

It is uncertain whether this story is legendary or factual. The Town’s local historian, Mary Miller Strauss, has provided this account on the settlement of Accident.

Hunters and trappers were the first white men to discover what is now the Accident Valley, located on the plateau of the Allegheny Mountains in Maryland’s western uplands. The vale and surrounding hills in the year 1800 were an area of gigantic growth of virgin timber. Here was a wilderness of beautiful broad-leaved trees and hemlocks. Under the thick growth of hardwoods and evergreens were the lush bushes of flowering rhododendrons and many species of ferns. The valley is drained by little streams flowing from its southern part into South Bear Creek and from its northern part into the mainstream of Bear Creek.

The Indians hunted here, camped here, and passed through, but never chose the site to build a village. There was one barely passable “road” known as Seneca Trail, a few other Indian Trails used for foot travel and pack horses, and a small house that probably was built by the Lamars sometime before 1798.

The Indians hunted here, camped here, and passed through, but never chose the site to build a village. There was one barely passable “road” known as Seneca Trail, a few other Indian Trails used for foot travel and pack horses, and a small house that probably was built by the Lamars sometime before 1798.

How did this spot get the name “Accident?” To this very day it remains somewhat of a mystery. There are number of stories advocating the name’s origin, but the following is probably the most nearly correct story of the “accident” at least it checks with the land records.

In 1774 Lord Baltimore, Proprietor of the Maryland Colony, opened his lands “westward of Fort Cumberland” for settlement, and among the speculators who hastened to western Maryland with their surveyors to secure choice tracts of land were Brooke Beall and William Deakins, Jr., both of Prince George’s County. William Deakins and his brother Francis had warrants for several tracts, and on April 14, 1774, they surveyed a fine tract of 682 acres between the branches of Bear Creek, including an old Indian camp ground on the trail to Braddock’s Road. But when the survey was completed, Brooke Beall and his party appeared on the scene and Beall claimed that he had selected the same tract for his survey, calling attention to his axe marks on the trees to prove his claim. Deakins replied that it appeared that they had selected the same land “by accident”. Since he and Beall were friends and land was abundant, he proposed that Beall take over the survey already made. To this Beall agreed, although his warrant called for 778 acres. John Hanson, Jr., Deputy County Surveyor, made out the survey to Beall, and they named the tract Accident.

Garret County

Some Historical Information About Garrett County, Provided by the Historical Society of Garrett County

Garrett County This county was separated form Allegany in 1872, and was named “Garrett” in honor of Mr. John W. Garrett, President of the B & O Railroad. Oakland was chosen as County Seat by a majority vote at the time of separation; it had been incorporated as a town in 1862.

This county was separated form Allegany in 1872, and was named “Garrett” in honor of Mr. John W. Garrett, President of the B & O Railroad. Oakland was chosen as County Seat by a majority vote at the time of separation; it had been incorporated as a town in 1862.

Old Voting Places

In the early 1800’s there were two voting places in this area. The one at Selbysport was called “Sandy Creek Hundred”. The second one, at Swantonk, was called “Glades Hundred”. Prior to the Revolutionary War, all for the land that comprises Garrett and Allegany counties was called “Skipton Hundred”.

Indian Trails

The County was criss-crossed with a number of Indian Trails. Modern names for some of them are Nemacolin Trail, Bear Camp Path, Seneca Trail, Blooming Rose Path, Ginseng Path, Friends Old Path, Pioneer Cumberland Road, Cuningham Road, Great War Path (McCullough’s Pack Horse Path, Glades Path, and Northwestern Trail.

Maps and Surveys  (1736) Benjamin Winslow was the first person to map parts of what is now Garrett County. Frances Deacon completed the survey of “Military Lots” in 1787, 4165 fifty acre lots were to be given as pay to Revolutionary War soldiers. The Mason-Dixon Line (northern boundary of the County) was surveyed in 1767,

(1736) Benjamin Winslow was the first person to map parts of what is now Garrett County. Frances Deacon completed the survey of “Military Lots” in 1787, 4165 fifty acre lots were to be given as pay to Revolutionary War soldiers. The Mason-Dixon Line (northern boundary of the County) was surveyed in 1767,

Fairfax Stone

(1746) Although located in West Virginia, it marks the meridian of the Maryland – West Virginia boundary.

Hoye Crest

Hoye Crest is located on the top of Backbone Mountain, and named for Captain Charles Hoye. It is the highest point in Maryland, being 3360 feet above sea level.

B & O Railroad

The railroad was completed through the county in 1851. Some 5,000 men worked on the section between Cumberland and Grafton.

Penn Alps

Known as Little Crossings during Colonial Times. Penn Alps is a unique gathering of log cabins, craftsmen’s booths, and a restaurant. In the area, a visitor can see the Casselman River Bridge (1813) and Stanton’s Mill (1794) the oldest continuous business in western Maryland.